Future Trends

|

Dec 31, 2025

AI is the Side Show, Disruption of SaaS is the Real Bomb.

In the age of AI, collapsing switching costs will shatter legacy SaaS business models, making way for usage and outcome based pricing, unleashing a long tail of composable software, and reshaping who wins in the next decade of software.

The Context

TV didn’t die because people stopped watching; it died because the business model stayed stubborn while the audience moved on. The same pattern is now playing out in software.

AI is blowing open production and distribution, but incumbents are still clinging to rigid seats, sleeper fees, and lock‑in. Instead of opening up, they’re doubling down on control—just as the ground shifts from centralized products to fluid, user‑owned stacks.

If you price software like it’s still 2015, this is the next decade’s playbook you’ll be competing against.

The Core Prediction

2026 will be the year usage‑based pricing goes from edge case to default.

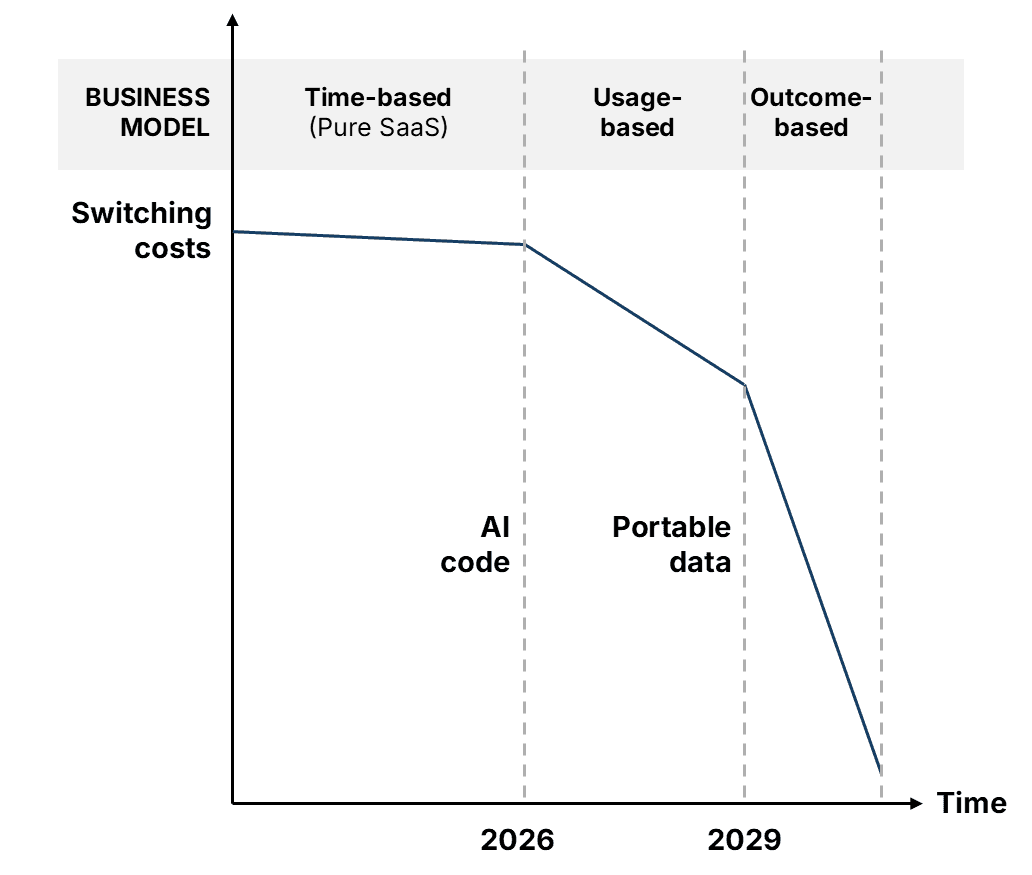

Many software companies will be forced to shift from time‑based subscriptions to pricing that tracks actual consumption—API calls, seats actively used, workflows run, storage consumed, decisions taken. The root cause is not “AI features” but collapsing switching costs: AI makes it dramatically cheaper to rebuild in‑house, easier to discover cheaper alternatives, faster to learn new interfaces, and far simpler to port data, content, processes, and users from one application to another.

Switching costs have always dictated which business models dominate software. Until around 2000, most software was sold like a car: you bought a perpetual license on a disk, often with a big upfront payment, and you were effectively locked in until you decided to “buy a new car.” Support and upgrade revenues depended more on release timing than on whether you actually used the product.

What are Switching Costs?

In software, switching costs come from three sources:

Learning curve cost

The time and effort for users to become productive on a competing service.Build cost (others or in‑house)

The cost to recreate comparable capabilities with alternative vendors or internal teams.Porting cost (data and connections)

The cost to migrate data, workflows, and integrations to the new service without breaking the business.

Each of these is now in structural decline:

Learning curve cost is falling because UX patterns have converged, UI frameworks are standardized, and AI copilots sit on top of any interface to guide users step‑by‑step.

Build cost is collapsing as low‑/no‑code platforms and AI code generators let small teams and even non‑engineers assemble credible alternatives in days or weeks, not quarters.

Porting cost keeps dropping as APIs, integrations, and AI‑assisted migration tools make it possible to extract, transform, and reload data—and even recreate workflows—across products with far less manual effort.

The combined effect is brutal: the default assumption shifts from “switching is too painful” to “staying is only rational if value keeps up.”

How Switching Costs Shaped SaaS

Business models follow switching costs. Before Salesforce popularized pure SaaS subscriptions in 1999, producers had limited control after the initial sale: distribution constraints, piracy, and one‑off licenses dominated. Subscriptions solved those problems by lowering the adoption barrier (no big upfront cheque), centralizing control in the cloud, and turning renewals into a predictable motion.

For two decades, this time‑based subscription model was win‑win enough. Switching costs were still meaningful: implementations were long, data was siloed, building in‑house was expensive, and learning a new tool was non‑trivial. Investors built an entire funding playbook around this world: ACV, net dollar retention, logo churn, LTV/CAC, and the implicit assumption that high switching costs would quietly protect incumbents. In many categories, medium to high switching costs were an excuse not to innovate; customers renewed because the alternatives were risky and painful, not because they were clearly better.

GenAI ends this complacent equilibrium. As AI‑generated code improves and gets cheaper, the cost to spin up credible alternatives falls off a cliff. As AI‑powered assistants onboard users, generate documentation, and sit between humans and interfaces, the learning curve shrinks from months to days. As AI‑driven migration tools and increasingly open APIs automate data and workflow moves, the historical pain of switching erodes.

Once switching costs fall below a certain threshold, time‑based pricing becomes untenable. Customers will no longer tolerate paying for “time on contract” when the vendor’s leverage has vanished. They will demand to pay only for what they actually use—and they will insist on eliminating sleeper fees and hidden overages. Vendors, in turn, will have to shift to usage‑based pricing or watch revenue evaporate as procurement treats every renewal as a fresh RFP.

Customer pull →

Business Model | Product License (First Model) | Pure SaaS: Time-based Subscription | Usage-based Fees | Outcome-based Commissions |

Switching Costs | High | Medium | Low | Zero |

Rationale | Early market users have less choice and will pay | Lower barriers to drive adoption and instead manage churn | Eliminate sleeper costs and innovate to capture usage | Offer for free and personalize to win and earn success based fees |

AI acts as software’s internet moment: a production and distribution shock that makes it trivial for anyone to build, ship, and remix software. Yet most vendors are simply bolting AI onto old SaaS shells—rigid seats, sleeper fees, and lock‑in—repeating TV’s error of protecting the channel while the audience moves on.

How Delivery Models Shift

As switching costs fall, software stops behaving like a rare product and starts behaving like a liquid, producer‑driven economy. The pattern mirrors the media's shift from a handful of TV networks to millions of creators.

Dimension | Institutional Era | The SaaS Startup Era | The Agentic Era |

Time Period | Before 2006 | 2006 - 2026 | 2026 and after |

Primary Business Model | Software as a Product | Software as a Service - Time based subscription | Usage or Outcome based pricing, DWY/DFY support |

Delivery Model | Disks/CDs with product licenses | Cloud based service siloes with authentication | LEGO-like modules that integrate with user’s stack |

Switching Costs | High | Medium | Low |

Control | Producers: Centralized vendor control | Platforms: App stores, plugin ecosystems | Users: User‑owned agents, personal stacks |

Scope | One‑size global suites | Localized vertical solutions | Hyper‑personalized workflows per user |

Market structure | Few large incumbents | Many niche SaaS tools | Millions of micro‑apps and solo operators |

Contracts | Locked‑in multi‑year deals | Monthly, cancellable subscriptions | Pure usage, no minimums, pay‑per‑event/API call |

Breakeven targets | High due to large central teams | Medium from contracting, and use of frameworks | Low due to AI |

Innovation tempo | Annual release cycles | Continuous deployment, fast follower copying | Open innovation, forking, remixing in real time |

Moat | Implementation and data lock‑in | Brand, ecosystem, network effects | Community, reputation, speed; almost no barriers |

No‑code and low‑code platforms are already pushing software in this direction, with a majority of new enterprise apps projected to be built this way and development time often cut by an order of magnitude. Communities like Makerpad and NoCode Founders function as “YouTube for apps,” where thousands of non‑developers share templates, automations, and micro‑tools that would previously have required a full product team.

Usage Pricing Driven by Demand

Usage‑based pricing actually has two very different anatomies, and only one of them is new. On one side are cost‑driven models like Twilio, Snowflake, or cloud infrastructure, where vendors have always charged per SMS, minute, API call, query, or gigabyte because their own costs scale almost linearly with usage. In these businesses, metering is primarily about covering variable cost and protecting gross margins, so usage pricing has been “native” from day one.

What is emerging now is demand‑driven usage pricing in categories where marginal cost is low but subscriptions leave money on the table. Tools like Adobe’s creative suite or Figma carry heavy R&D and product costs, yet the incremental cost of a user editing a few extra files is small; the real friction is psychological and contractual, especially for light or occasional users. As switching costs fall and “good enough” AI alternatives appear, these users become less willing to pay for a full month or year just to make a handful of assets. A usage‑based path—pay a small fee to export a high‑quality video, unlock advanced features for a single project, or run a limited batch of generative assets—would open up a long tail of creators who currently churn, pirate, or default to free tools.

This demand‑driven usage pricing is what will reshape the SaaS landscape over the next few years. It is not about covering per‑unit costs; it is about creating new markets among low‑frequency, price‑sensitive, and AI‑augmented users who resist traditional subscriptions. As more vendors in “Adobe‑like” categories adopt pay‑per‑project, credits, or export‑based models to capture this long tail, time‑based pricing will steadily retreat—from the edges of the market inward—until usage becomes the default expectation rather than the exception.

Low Defensibility Products Move First

Companies will not feel the pricing shock evenly. The first to move will be those whose products are easy to rebuild or replace with AI, and only later the complex, high‑defensibility systems.

Think of a spectrum:

On one end: narrow utilities like e‑signature, simple forms, basic image resize, transcription, boilerplate document generation. These are easy to recreate with off‑the‑shelf components, APIs, or an AI agent plus a bit of glue.

On the other end: rich, multi‑layered systems like Adobe’s creative suite or Figma’s collaborative design environment, where the moat is not just a feature set but years of UX iteration, ecosystem depth, file formats, plugins, and community.

The lower a product’s defensibility against AI, the closer it is to becoming a commodity—and the harder it is to justify locking users into time‑based subscriptions.

For low‑defensibility tools, users will increasingly see three options when a subscription renewal comes up:

Build an in‑house version with low‑/no‑code and AI helpers.

Use a “good enough” AI solution bundled elsewhere (e.g., inside their office suite or cloud provider).

Keep paying the subscription.

If those three options feel roughly equal in effort and risk, the subscription loses. The only way to stay in the game is to radically reduce commitment:

Let people pay only when they actually use the product.

Make the price per use small enough that the “should we rebuild this?” conversation never starts.

In a DocuSign‑style example:

A solo operator or small business asks: “Why am I paying a monthly fee for something an AI agent or a simple app could do?”

But if the service offers, say, a sub‑$5 fee to send one legally robust, audited, easy‑to‑track document for signature, the trade‑off flips.

The user no longer compares “subscription vs build my own”; they compare “a few dollars now vs hours of hassle and uncertainty.”

Usage‑based pricing here is not just fairer; it is a defensive shield against DIY and AI substitutes.

A Layered Transition, Not a Big Bang

The move from time‑based to usage‑based pricing is likely to roll out in layers:

2026: low‑defensibility utilities lead the shift

E‑signature, simple automation tools, commodity APIs, and narrow AI utilities (image generation, transcription, summarization) will pivot first.

Many will keep a “pro” subscription for power users but introduce a pay‑per‑use path to catch everyone else.

Near term: mid‑complexity products follow under pressure

As customers get used to usage‑based models at the edge of their stack, they will start demanding similar flexibility for mid‑tier tools: analytics dashboards, project management, marketing automation, customer support platforms.

Vendors in these spaces will likely adopt hybrid models (base platform fee + metered components) to manage revenue volatility while adapting to new expectations.

Later: high‑defensibility systems move last

Products like Adobe, Figma, or complex enterprise suites will feel the pressure more slowly because their value is deeper and replacement is riskier.

They may first experiment with outcome‑adjacent models (e.g., seats plus usage tiers tied to export volume, collaboration, or distribution reach), only moving to purer outcome models as integration and AI orchestration make switching even easier.

The key point: defensibility buys time, not immunity. Even the most complex systems are downstream of the same forces—AI reducing build cost, standardized UX reducing learning cost, and open data reducing porting cost.

New products will be usage‑based by default

New AI‑native products won’t wait to be pushed; they are already pulling the market toward usage and credits:

Many AI tools launch with a free tier plus paid credits for generations, calls, or automation runs.

This aligns perfectly with how users experiment: try something, see value, then ramp usage rather than committing to a plan upfront.

Founders designing from scratch see time‑based subscriptions as friction; they want their pricing to be as composable as their tech.

Over time, this creates a one‑way ratchet on buyer expectations. Once customers are used to:

Not paying when they’re not using, and

Scaling spend linearly with value,

they will be far less willing to tolerate subscriptions for low‑defensibility categories.

A New Playbook for a New Era

Generally:

If your product is easy to imitate with AI and standard components, usage‑based pricing is not optional; it is your best survival strategy.

If your product is complex and defensible, usage‑based elements are still worth introducing early—on your terms—before customers and competitors force your hand.

In all cases, the goal is the same: make the decision to stay so easy, so granular, and so obviously tied to value that “build our own” or “just use the free AI thing” rarely wins.

B2C: A transition from app stores to app builders

High‑fee app stores that skim 30% on distribution give way to near‑zero‑fee app builders plus communities that provide support and customization. No‑code tools let non‑technical users spin up apps in days, and low‑code platforms are on track to dominate the creation of new business applications. The next “app store” doesn’t sell downloads; it sells superpowers to build your own. In consumer software, the shift is from “download my app” to “fork my workflow.”

B2B: A transition from data moats to interoperability

In B2B, the collapse of switching costs shows up as a surge in usage‑based pricing and API‑first, composable stacks. A growing share of software firms expect consumption‑based models to become their primary revenue driver, while buyers increasingly prefer paying for what they actually use over fixed seats. Procurement is done paying for shelfware; they want Lego blocks, not glued‑together Lego sets. The new rule is simple: if I can’t get my data out in real time, I’m not putting it in.

The Rise of Composability

Skeptics point to 2025’s AI‑generated “spaghetti code” as proof that AI will never replace human developers: fragile scripts, missing tests, odd edge‑case failures, and systems that accumulate technical debt faster than a team can pay it down. But that is a snapshot of an immature stack, not the end state. 2026 is more likely to be remembered as the year low‑technical‑debt AI coding tools went mainstream—models that not only emit code, but also enforce patterns, generate tests, run static analysis, and refactor their own output against known best practices. As LLMs are trained on higher‑quality repositories, they increasingly generate code inside well‑defined frameworks rather than inventing structure from scratch: opinionated stacks, standard folder layouts, shared component libraries, and common data schemas. Human “vibe coders” converge on these stacks because they make AI output safer to review, easier to extend, and cheaper to maintain; over time, code that deviates from these norms is simply too costly to keep.

The pursuit of low technical debt becomes a gravitational pull toward a handful of dominant architectures and idioms, and the space for bespoke, hand‑rolled boilerplate shrinks dramatically.

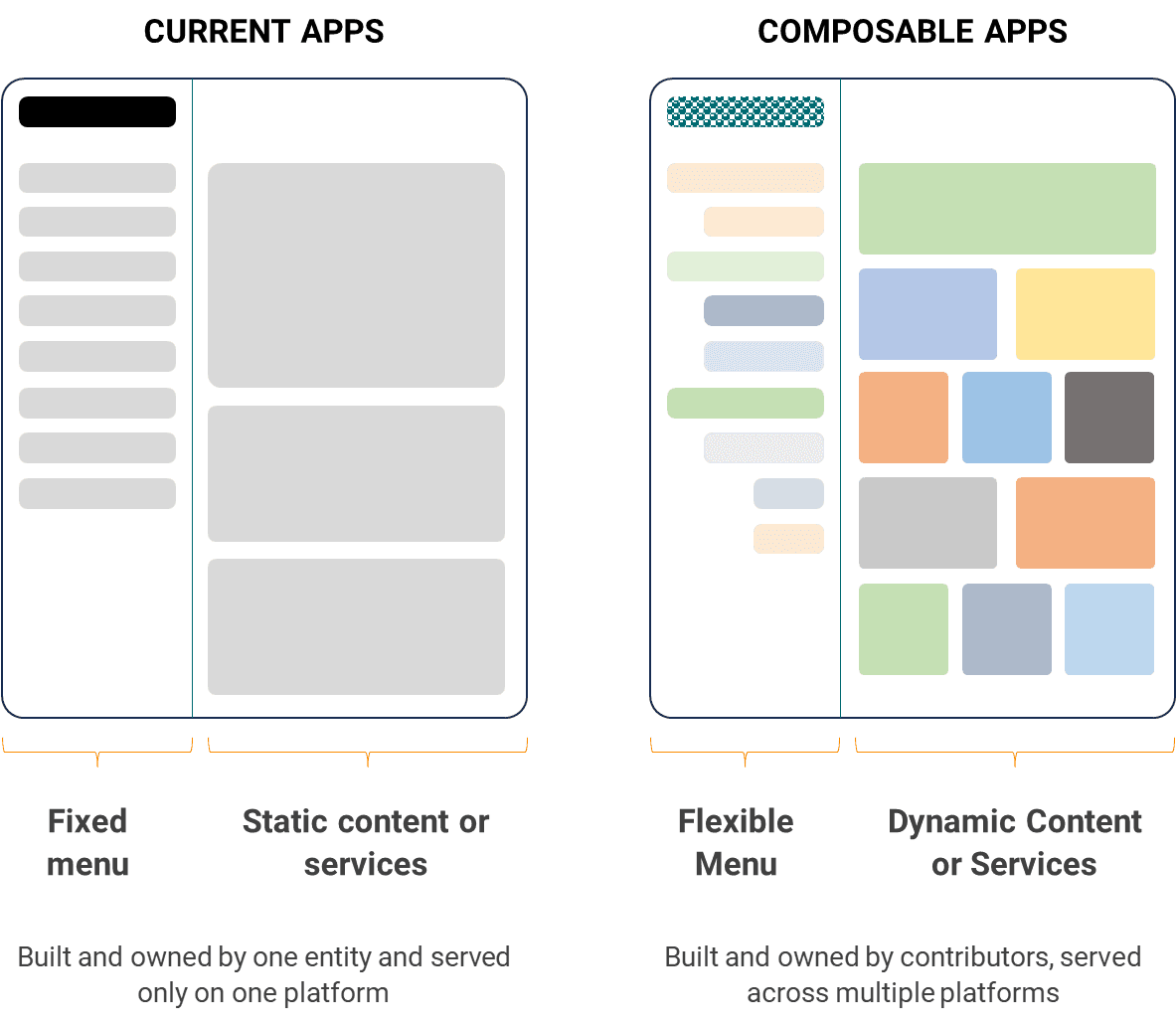

Once most new code is produced within these shared conventions—complete with auto‑generated tests, type checks, and migration scripts—reuse becomes the default; the same building blocks can be safely composed, swapped, and extended by millions of developers without collapsing under their own complexity. Rising composability and interoperability then redefine how software is built, owned, and monetized: AI‑accelerated modular frameworks push the center of gravity toward open‑source‑style components, maintained by communities and designed to plug cleanly into each other and into personal stacks. Early movers who ship high‑quality, low‑debt modules for free end up setting de‑facto standards for interfaces and data, which others adopt and extend. In that world, there will never be another Loom‑style billion‑dollar outcome for a single screenshot video app; instead, recording, sharing, and annotating video become cheap, composable primitives anyone can wire into their stack. Founders no longer guard one narrow feature—they create slowly maturing building blocks—while end‑users pay experts and independent creators to assemble and customize those blocks into bespoke workflows, with royalty flows back to original authors, much like music stems being remixed with persistent attribution and revenue share.

Flexible and Dynamic Interfaces of Composable Apps

The result is an ecosystem where solutions are highly composable by design: modules can be remixed, stacked, and swapped, while data stays in user‑controlled stores that follow common schemas.

Instead of founders building tightly guarded unicorns like a standalone Loom, they create slowly maturing building blocks that anyone can integrate; end‑users pay experts and independent creators to assemble, customize, and orchestrate those blocks into bespoke workflows—often with ongoing royalty flows back to original module authors, much like music being remixed with persistent attribution and revenue share. This evolution also blurs the line between open‑source and closed‑source: core components can live in the open, while paid hosting, premium add‑ons, and usage‑linked revenue shares create a “middle layer” where independent developers stay autonomous, contribute to shared ecosystems, and get paid fairly whenever their modules are used.

. Explosive Growth After Disruption

Time‑based SaaS will collapse, but software demand will explode.

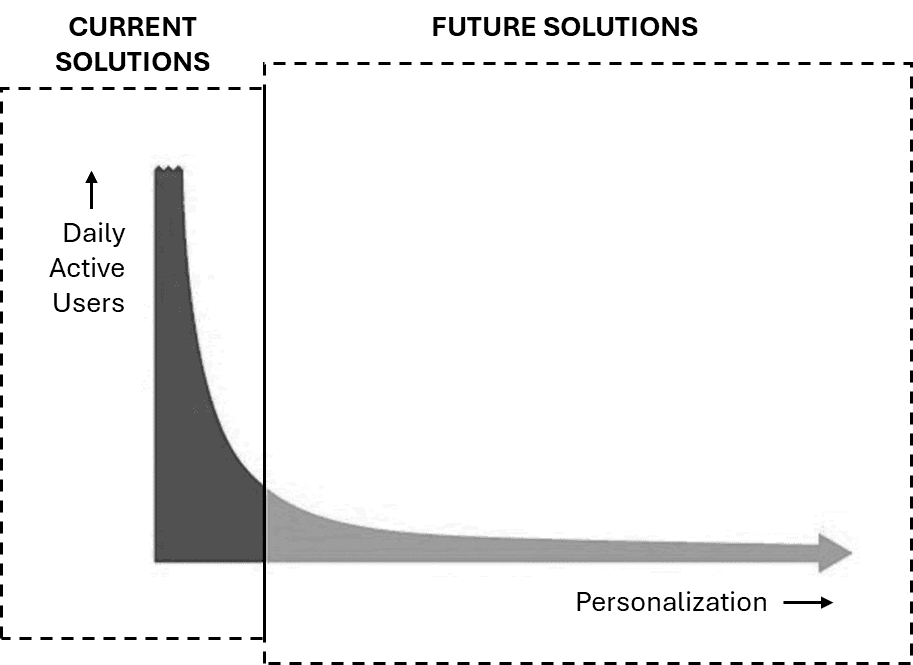

As prices fall and commitment drops from annual contracts to per‑event or per‑outcome fees, millions of use cases that were never “worth a subscription” suddenly become viable: tiny internal tools for a single team, one‑off automations for a project, hyper‑niche workflows inside professions that software largely ignored until now. Instead of a few big subscriptions, the landscape tilts toward billions of small, granular interactions—API calls, document runs, agent tasks—each billed in cents or slices of outcome, and each snapping into a composable ecosystem rather than a monolithic suite.

The Long Tail of Personalized Solutions

This is Jevons’ paradox in action.

When something becomes radically more efficient and cheaper, total consumption often rises instead of falling, mostly due to the potential to capture a long tail of use cases that were not economically viable before—and software will follow that script.

AI slashes the cost of building and running services, usage‑based pricing removes the psychological and financial friction of “yet another subscription,” and composable architectures make it trivial to wire new tools together. The result is not less software, but far more: an enormous long tail of micro‑apps and agents stitched into documents, chats, and devices, all pushing the industry deeper into usage‑priced, interoperable ecosystems even as the old SaaS revenue model withers.

. Beyond 2030

Push this logic forward a few more years. At some point near the end of the decade—call it around 2030—switching costs in many categories will approach zero.

True interoperability, composability, and user‑owned data will mean that:

Any workflow can be re‑composed across tools in hours.

Any dataset can be pulled into any agent or application on demand.

Any interface can be swapped without serious retraining because AI intermediates between human intent and software actions.

In that world, even usage‑based pricing becomes fragile. If customers can switch between near‑identical utilities in real time, they will expect software to be free at the point of use and priced instead on outcomes: revenue generated, cost saved, time reduced, risk mitigated, or opportunities captured. Vendors will have little choice but to offer deeply personalized solutions and then take a transparent slice of the “winnings”—success fees, revenue share, or income‑linked models—because metering commodity usage will no longer be defensible.

GenAI is the engine moving the industry from time‑based subscriptions to usage‑based pricing. Portable, user‑controlled data is the engine that will move it from usage‑based to outcome‑based models.

Customers end up with unprecedented power: the ability to remix tools at will and pay only when value materializes. Companies that are confident in their capacity to drive those outcomes will thrive; those that rely on locked‑in time will not survive the decade.

The Myth of 1‑person Unicorns

The “1‑employee unicorn” is the wrong fantasy. Falling costs from AI do not mean a single person will build the next Salesforce; they mean a single person can run a real, profitable micro‑business on top of modular tools, usage‑based infrastructure, and outcome‑based services.

AI collapses the cost of building, hosting, and operating software, but it also collapses prices as competition and composability increase. Instead of throwing off billions in enterprise value from one tightly guarded app, the new archetype is a solo or tiny team that assembles open components, leans on usage‑priced platforms (for compute, payments, AI, distribution), and sells highly personalized solutions or done‑for‑you outcomes to a narrow audience. These creators make money precisely because they are lean enough to live on thin per‑use or revenue‑share margins that would never sustain a traditional venture‑scale SaaS company.

In this world, AI reduces the minimum efficient company size far more than it increases the maximum company valuation.

The real shift is from a few giant, headcount‑heavy vendors to millions of small, agent‑ and AI‑powered specialists plugged into composable ecosystems—each monetizing a sliver of value through usage‑ and outcome‑based pricing, rather than chasing the myth of a one‑person unicorn.

The Real Winners and Losers

Winners will be open, composable, AI‑native platforms and independent creators aligned with user outcomes, while losers will be closed, sleeper‑fee SaaS incumbents clinging to lock‑in and network myths.

Winners

AI‑native open systems with ultra‑low fees

Think “FAST TV for software”: free or near‑free access, monetized through scale, marketplaces, and adjacent services. Winners don’t meter access; they meter outcomes.Usage‑based services with zero sleeper fees

These products keep customers by letting them turn the dial up and down instead of forcing a binary churn decision. In this world, churn doesn’t mean leaving; it means turning the knob down, then up again when value returns.An army of independent creators and service providers

No‑code ecosystems empower solo “integrators” who stitch together agents, APIs, and components for specific users and niches. The next SAP integrator is a single person with a no‑code stack and an agent farm.

Losers

Sleeper‑fee SaaS with dark patterns

Products that depend on long commitments, auto‑renewals, and overage traps will be the first to be cancelled when switching is cheap. If your revenue depends on people forgetting they’re subscribed, your days are numbered.Network‑effect absolutists

Relying solely on network effects while ignoring openness and speed will fail once users can route around you. Network effects are a shield, not a strategy.Closed systems that lock out developers

Platforms that do not expose real APIs or share revenue with ecosystem builders will be bypassed by those that do. If developers can’t build on you and bill through you, they’ll build around you.

Who Needs to Adapt—and How

Investors, founders, tech giants, and infra players must abandon old seat‑based SaaS reflexes and design around usage, outcomes, and composability—or risk being optimized out of the new stack.

Investors: Stop underwiting old SaaS physics

Mid‑tier SaaS funds now deploying Fund II or III are most exposed: their instinct will be to double down on seat‑based, lock‑in‑driven playbooks just as usage‑based, composable software erodes those moats. Mega‑funds will make many of the same mistakes, but their broad indexing means they will accidentally back a few outliers that define the new era. Smaller, emerging managers with operator DNA are structurally better positioned: they can pivot theses quickly, back weird composable and usage‑native models, and ride the upside of a playbook the older funds are still dismissing.Founders: Aim for ecosystems or extreme niches

The founders who win will either build ambitious platforms that assume composability—open standards, modular products, usage‑ or outcome‑based pricing—or they will go very narrow, owning specific long‑tail problems that only become viable when software is cheap and modular. “Middle of the road” SaaS—generic apps with generic pricing and shallow moats—gets crushed between open components below and deep ecosystem plays above.Tech giants: Build bridges, not walls

Incumbent giants will be forced to choose between becoming hubs in a composable ecosystem or defending fortresses whose walls are quietly being tunneled under. Winners will open data, APIs, and revenue‑sharing programs, accepting that value now comes from orchestrating modules and partners rather than locking users in. Those who cling to closed stacks, network‑effect myths, and rigid pricing will keep revenue for a while—but watch the next generation of developers and integrators build around them instead of on them.Software‑adjacent players: Short‑term boom, long‑term compressionCloud infrastructure providers and hardware leaders like GPU vendors stand to benefit first: commoditized software and exploding long‑tail demand translate into more compute, more storage, and more networking. But as ecosystems mature and local players apply the same composable, efficiency‑obsessed culture to hardware and infra, even these layers will face price pressure and fragmentation; the culture of open standards and modularity will not stop at the software boundary.